Chapter 6

CHINA and KOREA

China

Buddhism was transmitted to China along the Silk Route in the early centuries of the Christian era, and over the next millennium the sacred texts were translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by learned monks and scholars from India, Central Asia, and China. In the early fifth century, for example, Kumarajiva (348-417), a native of Turkestan, established a translation bureau of one thousand monks in Changan (modern Xi’an), at that time the capital of the Later Qin Kingdom. Half Indian, half Kuchean, he had studied Buddhism in Kashmir and Kashgar and was in great demand both in Kucha and at the courts of various Chinese rulers. Though he tried to remain faithful to the original texts, he is supposed to have said that reading sutras in translation is like eating rice that someone else has already chewed.1 Not only did Chinese Buddhists assiduously translate the Indian texts, but many of the latter are known today only from the Chinese translations. The Chinese Canon, or Tripitaka (the Buddha’s sermons, the monastic rules,and the higher philosophical treatises),grew to include 1,662 separate scriptures. It was from China that Buddhism was introduced into Korea in the fourth century and into Japan in the sixth. Both countries regarded Chinese Buddhist texts as canonical and read them in Chinese script. The Japanese, for example, did not translate the Tripitaka into their own language until the beginning of this century.

With the exception of authors who published in English, all Japanese, Korean, and Chinese personal names are given in the traditional East Asian manner, with the family name first.The oldest Buddhist manuscripts in East Asia were accidentally discovered by the Hungarian-born, British scholar- explorer Sir Aurel Stein (1862-1943) in 1907 in a sealed cave at Dunhuang, a Buddhist site in Gansu Province on the eastern end of the Silk Route.2 The spectacular cache was walled up in the eleventh century, probably to prevent the sacred works from falling into the hands of barbarian tribes who threatened to overrun Dunhuang (fig. 83). The contents of this treasure trove (containing manuscripts in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Central Asian, and even unknown languages as well as hanging scrolls and banners) date from as early as the fifth century and are of great significance both for Buddhism and the history of the book in Asia. Most early Chinese Buddhist materials were destroyed in the mid ninth century during a wave of anticlericism, which resulted in the closure and destruction of tens of thousands of Buddhist temples and shrines throughout the country. The temples and caves of Dunhuang, which had fallen into Tibetan hands at that time, were saved. The arid desert climate contributed further to the preservation of these fragile works on paper and silk. Stein purchased seven thousand complete manuscripts from the hidden library and a further six thousand fragments (the bulk of which are in Chinese) as well as innumerable paintings for the collection of the British Museum and British Library, London. A second sinologist, Paul Pelliot, arrived the next year to acquire additional works for the French government.

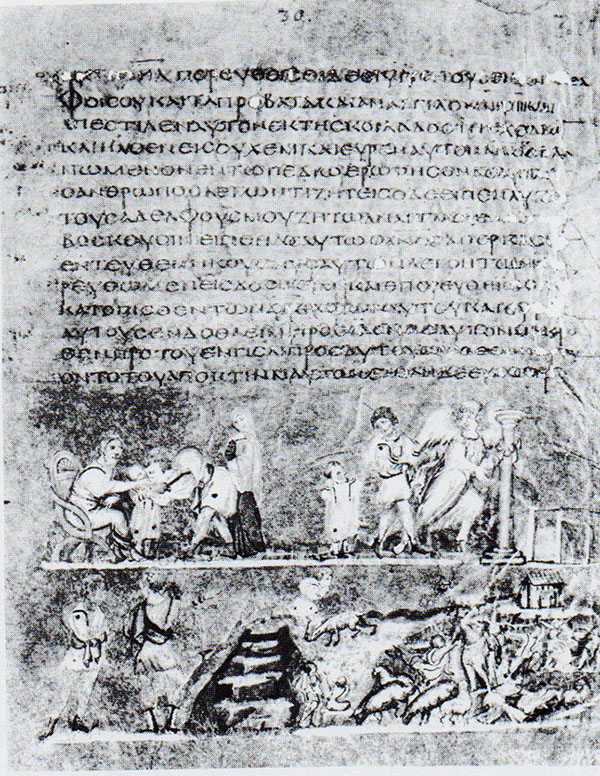

In East Asia sutras are usually written in ink on paper and commonly take the form of long horizontal handscrolls formed by pasting together a succession of sheets. The roll format had been used first in the ancient West (fig. 84). The Egyptians had written their Book of the Dead on papyrus rolls averaging thirty to thirty-five feet long. When the famous library of Alexandria burned at the time of Julius Caesar, it was said to have contained seven hundred thousand papyrus scrolls, many of which must have been illustrated. The roll format was eventually judged inconvenient and cumbrous, however, and was supplanted in the ancient world by the bound book, or codex, introduced in the second century A.D. The use of papyrus soon gave way to that of parchment, or vellum, produced from the skin of cattle, sheep, or goats. Flat parchment sheets permitted the application of thicker layers of paint and invited enlargement of single scenes, thus leading to a florescence of miniature painting The earliest surviving Bible illustrations were produced in a scriptorium in Rome in the early fifth century.3 Although bound books and accordion- pleated, folding books also came into use in East Asia, they never entirely replaced the handscroll.

In East Asia sutras are usually written in ink on paper and commonly take the form of long horizontal handscrolls formed by pasting together a succession of sheets. The roll format had been used first in the ancient West (fig. 84). The Egyptians had written their Book of the Dead on papyrus rolls averaging thirty to thirty-five feet long. When the famous library of Alexandria burned at the time of Julius Caesar, it was said to have contained seven hundred thousand papyrus scrolls, many of which must have been illustrated. The roll format was eventually judged inconvenient and cumbrous, however, and was supplanted in the ancient world by the bound book, or codex, introduced in the second century A.D. The use of papyrus soon gave way to that of parchment, or vellum, produced from the skin of cattle, sheep, or goats. Flat parchment sheets permitted the application of thicker layers of paint and invited enlargement of single scenes, thus leading to a florescence of miniature painting The earliest surviving Bible illustrations were produced in a scriptorium in Rome in the early fifth century.3 Although bound books and accordion- pleated, folding books also came into use in East Asia, they never entirely replaced the handscroll.

The earliest illustrated manuscript from among the finds at Dunhuang is a printed Diamond Sutra (Vcijrachchhedika Prajnaparamita) dated A.D. 868. Known as the world’s oldest printed ‘book’, it is displayed in the British Museum only a few paces from the West’s most famous book, the Gutenberg Bible. It must be emphasized that since so few illustrated Buddhist manuscripts and fragments have survived from this early period, a coherent survey cannot be written. There are still enormous gaps in the history of what must have been the most creative and prolific age of sutra illumination in China. Moreover, the surviving works are not necessarily of the finest quality. Dunhuang, where so many early Chinese sutras were deposited, was located far from the major centers of Buddhism in China. Inevitably, the portable scrolls and booklets that were preserved here are often slightly clumsy, provincial versions of the now-lost works created by masters at the great temples in Changan, Loyang, and the other cities in metropolitan China. Moreover, they were commissioned by individuals of varying means, and it is evident that not everyone could afford the finest workmanship.

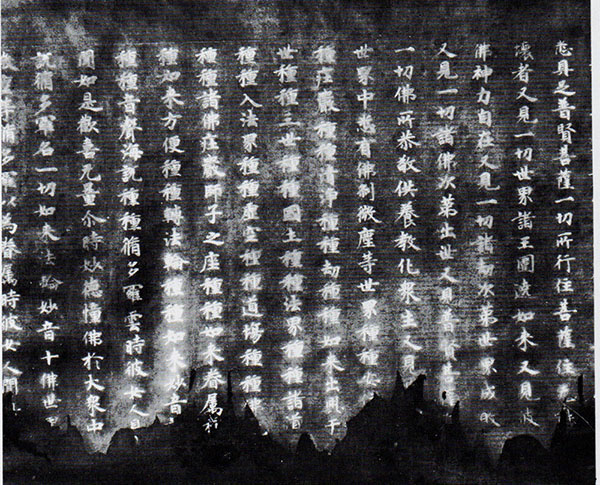

Occasionally, scriptures were transcribed in the shape of a stupa, or pagoda. In figure 85 the Heart Sutra, an abbreviated version of the great Prajnaparamita, is written on a single sheet of paper. This custom was continued later in both Korea and Japan, where much longer texts were written in the form of towering, multistoried pagodas and other pictorial designs.

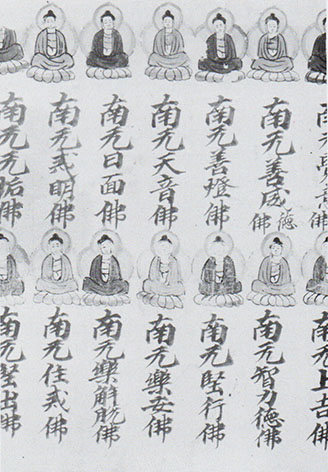

An early tenth-century manuscript with a simple, but effective method of illustration is the Sutra of Buddha’s Names,which enumerates the Thousand Buddhas of the present age (fig. 86). Written from top to bottom and right to left (as customary for Chinese and Japanese manuscripts) each name is preceded by a tiny and rather charming Buddha in regularly alternating colors.

The Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapundarika) outnumbers all others represented at Dunhuang, whether in the form of wall paintings, hanging scrolls, or manuscripts. The sutra was composed in northern India or possibly Central Asia during the first and second centuries A.D. Although Sanskrit originals of the early forms of this text do not survive, there are three early Chinese translations. The standard version used today is based upon the translation of A.D. 406 by Kumarajiva, who is said to have worked from an original written on fabric in the Kharashar script of his native Kucha.

Proclaiming itself to be the king of sutras, the final, most complete and perfect revelation of Buddha Sakyamuni’s teaching, the Lotus Sutra is more emphatic than others in its delineation of the basic Mahayana doctrines of universal salvation and the eternal Buddha. The text, organized into twenty-eight chapters,, is believed to contain Sakyamuni’s final sermon at Vulture Peak. Here he preaches the truth that all persons, monks and ordinary laymen alike, can attain salvation instantly. Even Hinayana Buddhists, women, and the worst sinners, such as the Buddha’s evil cousin Devadatta are included. Difficult doctrinal points are clarified for the layman with graphic and easily understood parables; the saving powers of the Buddha, for example, are likened to the gentle rain that falls equally on large trees and small grasses. The many interesting stories, combined with the relative brevity of the text, surely contributed to its popularity. Also important to the success of the Lotus Sutra was the prominent role it attributed to two of the mightiest and most beloved of the great savior bodhisattvas, Avalokitesvara and Samantabhadra, who make their appearances in Chapters 25 and 28 respectively.

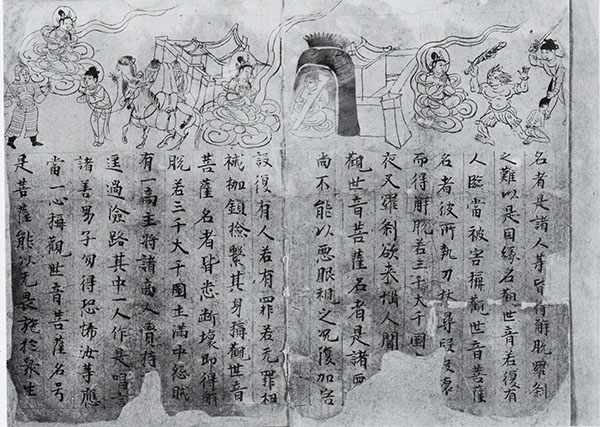

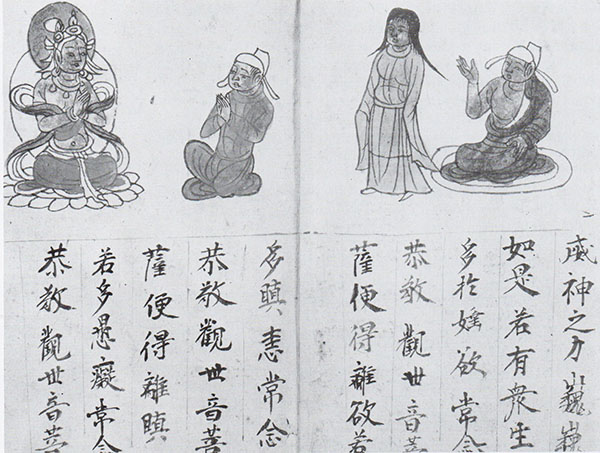

Two early booklets from Dunhuang in the British Library take as their text Chapter 25 of the Lotus, which was often treated almost as an independent scripture (figs. 87-88). The chapter is devoted to the miraculous saving powers of the compassionate bodhisattva who has vowed to heed the cries of the world. In an age of 'international travel Avalokitesvara was invoked by those embarking on long and arduous journeys, whether by caravan across the bleak expanse of Central Asia or by boat across the stormy seas. Even modern visitors to the caves of Dunhuang will readily appreciate the pictorial prominence given to this theme in wall paintings from as early as the sixth century and in hanging scrolls and banners from the same site, which date from the ninth or tenth century. Pilgrims and merchants stopping at this desert oasis on the westernmost border of China faced a long trek across an inhospitable desert, where they were certain to encounter bandits and wild beasts. They needed all the help they could muster.

Chapter 25 is divided into three major sections. The first enumerates the perils from which believers will be delivered and wishes that will be fulfilled if they but call upon the name of the bodhisattva. Every contingency seems to be accounted for:

- Falling into a great fire

- Carried away by a great flood

- Shipwreck in a land of cannibalistic demons

- Menace of an attacker’s sword

- Attack by demons (yakshas and rakshasas)

- Punishment by fetters

- Merchants attacked by robbers

- Temptation of lust

- Attack of anger

- State of delusion

- Desire for a male or female child

- Desire for happiness and prosperity

In the second section we learn of the so-called thirty-three (actually thirty-five) disguises assumed by Avalokitesvara in order to assure that his appearance, when he preaches, precisely suits the circumstances. In the third section the perils enumerated earlier are reiterated in verse form and expanded.

In the Dunhuang booklets here reproduced the illustrations, drawn with cartoonlike simplicity and directness, are all at the top of the page immediately above the text. Perils 4 through 7 are readily identifiable in figure 87. On the right are the menace of an attacker’s sword, the threat of a club- wielding demon, and punishment by fetters. On the left a bandit in full suit of armor approaches a merchant leading his horse and camel away from the safe confines of a walled city. The bodhisattva makes a miraculous appearance each time the victim prays for divine intercession.4 The drawing in figure 88, probably executed with a simple wood brush or reed pen and supplemented with red and yellow pigment, is even more rudimentary.5 On the right a devotee, partially undressed, gestures toward a buxom beauty in a diaphanous gown. On the left he is saved from sinful thoughts by meditating respectfully on the bodhisattva. It is the eighth peril, temptation of lust.

Unlike the dramatic, large-scale murals at Dunhuang, the pocket-size booklets were intended for private devotional use, for personal salvation. Typically, a sheet of thick paper was folded to form the pages of a booklet, with the corners cut or rounded. The folded pages might be pasted together along the edge of the center fold, or sewn, or even left separate.

Imagined torments in the afterlife are alleviated through the intercession of Kshitigarbha, another of the great bodhisattvas. Many paintings on silk and paper from Dunhuang attest to the rising popularity of this deity in the tenth century. Although shown alone at first, he is soon depicted together with the Ten Kings of Hell, who eventually replace him as the main subject. The Ten Kings of Hell Sutra was apocryphal and seems to have been composed in China during the tenth century. It describes the ten stages through which the soul must traverse after death. The soul passes before the first of the ten kings of the underworld on the seventh day after death and successively thereafter on each seventh day until the forty-ninth and after that on the hundredth day and again on the first and third anniversaries of his death. Each king is seated behind a draped table, attended by the recorders of a person’s good and evil deeds who stand by wearing suitably smug expressions. The scroll illustrated here (Pl. 70) opens with a messenger riding a black horse who comes to inspect the merits performed by the families of the deceased.6 In this detail King Chujiang, who presides at the second tribunal, or the second seven-day interval, gazes sternly at a virtuous soul holding a scroll and bowing abjectly before him. Sinners, by contrast, are clad only in loincloths and wear wood cangues. The artist has obviously taken as his model the terrifying world of a tenth-century magistrate’s court and the hellish reality of Chinese bureaucracy. At the end of the scroll Kshitigarbha stands just outside the gate of a walled, prisonlike structure representing hell. Inside, a poor soul is pinioned on a bed of hugh spikes and engulfed by flames. The gentle bodhisattva, dressed as a monk, has come on a mission of mercy to rescue tormented souls. Here, again, the artist, although lacking technical skill, delights in expressive gestures and his images convey the message of the sutra with a forcefulness that all but overshadows the written word.

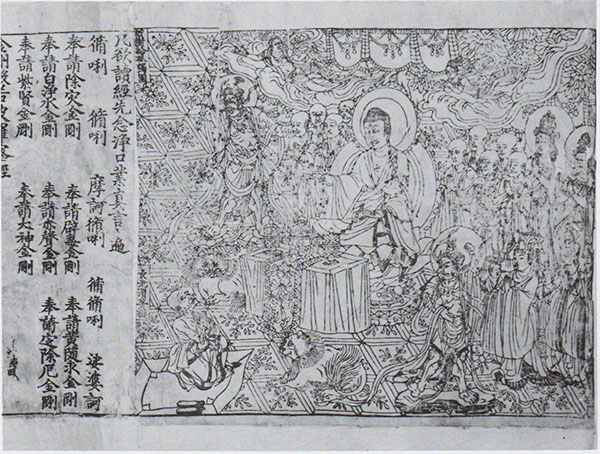

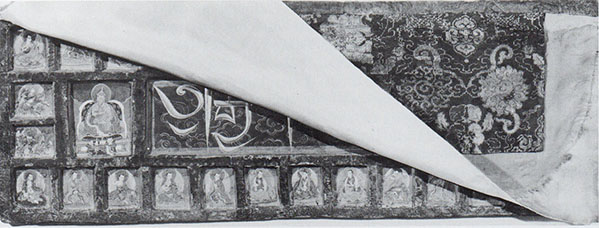

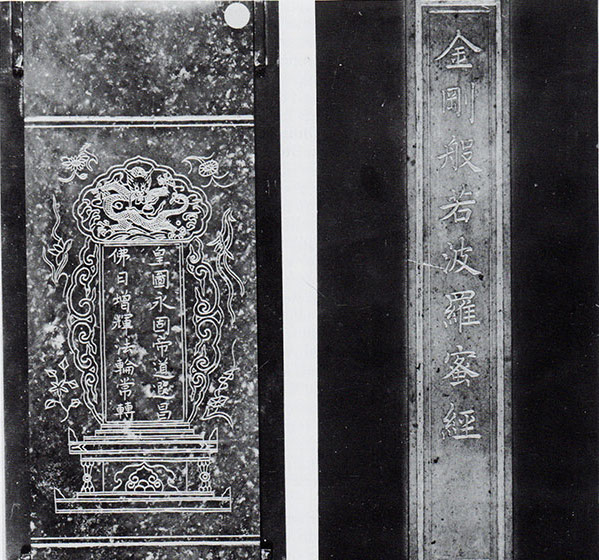

Among the most charming of the Stein manuscripts is a booklet containing Kumarajiva’s popular translation of the Diamond Sutra (Pl. 71). At the beginning of the booklet are images of the eight Diamond kings, followed by the frontispiece showing Buddha Sakyamuni, surrounded by his retinue of attendants, instructing his disciple Subhuti in the Perfection of Wisdom at Jetavana Monastery. The monk kneels on the ground on a small mat in an attitude of reverence. The first text page, on the left back side of the scene, begins with the words: “To be held in the hands and intoned.”7 The modest little painting of the Buddha preaching is delightfully fresh and spirited; its crowded composition suggests the richness of the setting, and abrupt differences in scale are presumably a naive attempt to convey spatial recession.

The scene is virtually the same as that of the famous frontispiece to the woodblock-printed Diamond Sutra in hand- scroll form dated 868 (fig. 89). In both examples the Buddha, enthroned on a raised lotus pedestal behind a draped altar, faces leftward, toward the text, and the blossoms of a flowering tree form a canopy overhead.

There is much textual evidence for early printing from carved wood blocks in China, although documentary specimens are rare. The earliest extant item is a Sanskrit charm with a six-armed bodhisattva printed on a single sheet and dated 757. Max Loehr believes that “evidence still points to China as the place where in all likelihood the written word was first printed. Here there was a long tradition of handing down texts in manuscript or epigraphic form, and an abiding concern for scriptorial matters quite generally that led the Chinese to search for, and invent, the perfect medium of brush, ink, and paper.”8 Printing activity flourished by the tenth century, when the government undertook to edit and print the Chinese classics, an endeavor that required twenty- one years of labor, and “by the beginning of the eleventh century, printed books were as common in China as they would be six centuries later in the West.”9

The printing of many sutras is recorded for the ninth century, marking the beginning of a close interaction between printed and painted illuminated manuscripts. Because printing allowed for wide dissemination of illustrated texts, these easily accessible works quite naturally began to serve as models for painters. The printed Diamond Sutra found at Dunhuang is far more elaborate and sophisticated than the painted booklet and was probably produced somewhere in metropolitan China. Its dated colophon states that the scroll was made by order of Wang Jie for the welfare of his parents. The Buddhist emphasis upon earning merit by repeating prayers and charms certainly encouraged the spread of printed books in China as it did in Korea and lapan, where printed eighth-century dharani texts have been found. Printing itself implies repetition, and the distribution of large editions of the Diamond Sutra was an act of merit, even if they were not copied by hand.

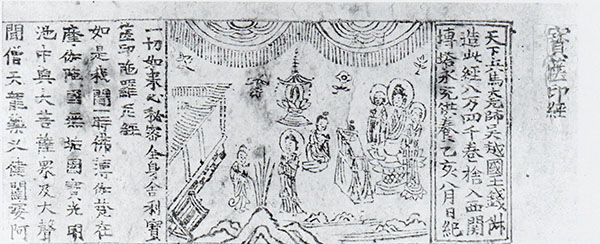

The multiple printings of the so-called Thunder Peak Pagoda Sutra illustrate this point most dramatically. The fifth prince of the Wu-Yue Kingdom, an ardent Buddhist, built a pagoda, later known as the Thunder Peak Pagoda (Leifangta), in 975 on the West Lake at Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province. To commemorate this monumental undertaking he commissioned the printing of a great many miniature sutra scrolls embellished with unpretentious frontispieces in what has been characterized as provincial folk style (fig. 90). When the pagoda sank into a shapeless mound of bricks on the afternoon of September 25,1924, it was found that the donor had deposited the scrolls (as many as eighty-four thousand, if we can believe the dedication at the beginning of each roll) inside the hollowed bricks. The number apparently symbolized the eighty- four thousand relics of the Buddha’s body.10 The frontispiece illumination, framed by a fringed curtain, includes a small stupa, two lay figures worshiping a seated and a standing Buddha, and the edge of a temple wall.

Inscriptions by donors often attest to their desire that the printed sutras achieve permanent circulation. “May these texts circulate forever,” wrote one pious devotee.11 In the 970s Emperor Taizu (r. 960-75), making an effort to revive Buddhism after the persecutions of the mid ninth century, ordered the printing of the first Buddhist canon, an effort requiring 130 thousand wood printing blocks. Although it has long since been lost, this first edition of the printed canon was illuminated. Sets were sent to neighboring countries in part as a meritorious act but also to increase political goodwill and enhance China’s cultural prestige. Later the canon was privately printed by monasteries not under government control and sold for profit.12

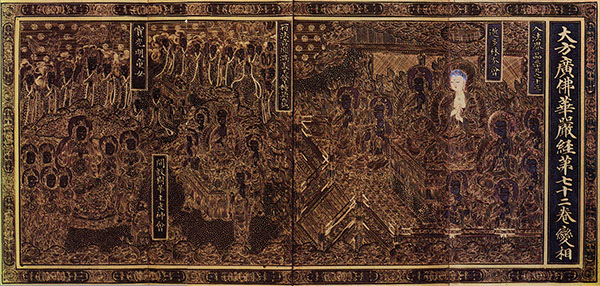

Handwriting was not wholly replaced by printing, however. It is recorded that in 972 the Song emperor ordered several canons in gold and silver characters on indigo-dyed paper in gratitude for recent military victories. A rare extant set from this early period is a seven-volume Lotus Sutra with illustrations in gold on indigo commissioned by the younger brother of the prince who built the Thunder Peak Pagoda.13 Sutras written in gold or silver on glossy, high-quality deep-blue paper were known even in the Tang dynasty (618-906): the well-traveled Japanese monk Ennin (794-864) observed several sets of the Tripitaka at the great monastery on Wutaishan, but such works are now scarce in China.14 Their appearance can be surmised from the large body of well-preserved eighth- century Japanese copies. There was a large bureau of sutra copying in the imperial palace compound in the capital at Nara and more than 250 professional scribes, supported by the imperial family, labored in the Hall for Copying Buddhist Texts at Todaiji, the vast temple complex dominating the capital that served as headquarters for a nationwide network of state-supported monasteries.15 In 741, sets of the Radiant Victorious Kings Sutra (Suvarna-prabhasottamaraja-sutra) written in gold on purple were prepared at the order of Emperor Shomu in the newly established Bureau of Gold Character Sutras for distribution throughout the country to ensure the peace of the nation.16 Specialists who wrote with gold and silver inks were among the highest ranking and highest paid copyists. This medium was not only costly (gold powder was imported) but difficult (the granular powders are much less fluid than regular ink). Figure 91 illustrates a segment of an Avatamsaka Sutra from a large set of eighty scrolls believed to have been donated to the Todaiji in 744 for the first annual Avatamsaka ceremony, a festival for the worship of this sutra. The style of the calligraphy also accords with a date in the first half of the eighth century. It closely follows the rigorously disciplined, academic style of Chinese formal or regular script of the early Tang dynasty in the seventh century. The earliest transcriptions in Japan have neither frontispiece paintings nor decorative marginal ornamentation, perhaps because the written word itself was still regarded as of primary importance.

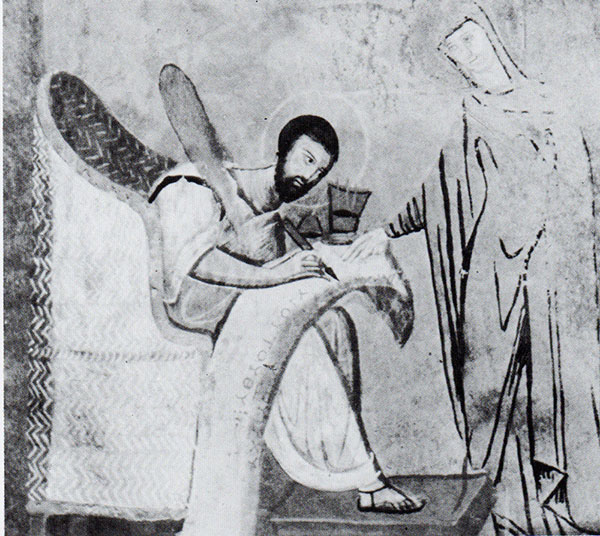

There is no doubt that the gorgeous technique (along with almost every aspect of Japanese culture in the seventh and eighth centuries, including the written language and Buddhism itself) was imported from China. The origins of the technique, however, lie in the world of late antique and early Christian book illumination, transmitted to China, one supposes, via Nestorian Christians or merchants crossing the silkroutes of Central Asia. Though popular as early as the fourth century, the earliest surviving purple codices are the lavishly illustrated Vienna Genesis and the Rossano and Sinope Gospels (figs. 84 and 92).17 Written in splendid silver uncial script (with an occasional word picked out in gold) on purple vellum, they were produced in either Antioch, Constantinople, or Jerusalem (the exact place of origin is still debated) in the sixth century. Purple codices were sheer luxury items commissioned by rich lay donors—once the silver script tarnished, the manuscripts were very hard to read. The illustrations, possibly copied from monumental murals, are often placed at the bottom of the page and employ the device of continuous narration, in which the same figure reappears several times in successive scenes—a style of narration exploited later with great success in the Japanese handscroll. In figure 92 the episode of Joseph being sent to Shechem is depicted in four scenes: in the upper register, for example, we see him bending down to kiss little Benjamin farewell and on the right he is led off by an angel.

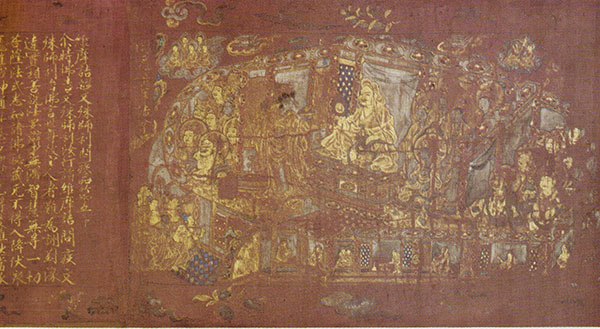

AVimalakirti Sutra handscroll in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is exceptional for its use of silk, rather than paper, and costly gold and silver pigments on purple, the color of royalty (Pl. 72). This remarkable work, which was evidently highly valued, is one of several twelfth-century paintings surviving from the Dali (Ta Li) kingdom. The Nan Zhao and Dali kingdoms flourished successively from the midseventh to midthirteenth century (when the latter was sacked by Kublai Khan) in what is now Yunnan Province in southwest China, bordering Burma, Laos, and Vietnam. Dali Buddhism and artistic styles were heavily influenced by continuous interaction with Song Chinese culture.

The Vimalakirti scroll closes with a colophon dated in accordance with January 1119, which states that ifs production was supervised by the abbot of Fuding (Buddha Head) Monastery on behalf of the hereditary prime minister of the later Dali kingdom, Gao Taiming, who made a present of it to visiting Chinese ambassadors returning to the court of the Song Emperor Huizong (r. 1101-25), the well-known patron of the arts:

The prime minister of the Dali kingdom, Gao Taiming, prepared this section of the Vimalakirti Sutra for the ambassadors of the Great Song Dynasty, Zhong [Zhen and Huang Jian], and hopes that they will be successful in carrying out their mission and will return safely to their court,that they will receive blessings and emoluments, and will be free from fear and danger in crossing the mountains and taking so long a journey. May they receive the divine favor to the end that China and the distant kingdom (Dali) henceforth for a thousand myriad years may never break off relations.18

The story of the visit of Bodhisattva Manjusri to Vimalakirti on his sickbed held particular appeal for the Chinese and was featured in early wall paintings at Dunhuang. Chinese generally eschewed monasticism in favor of family life -and worship of ancestral spirits. With its emphasis upon the layman, this sutra suited the Chinese view. A rich Indian layman, Vimalakirti, was skilled at argument and had a profound knowledge of the Buddha’s teachings. "When the Buddha asked his disciples to go and enquire after Vimalakirti’s health, they refused one after another, recalling previous occasions when he had outwitted them. Finally Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, agreed to go, and a great concourse assembled to hear their discussion, which covered subjects such as the nature of non-duality, and the illness of a Bodhisattva. The debate ends with Manjusri expressing his unqualified admiration for the depth of Vimalakirti’s knowledge”19

Pl. 73. Buddha

Preaching the Law, frontispiece to a Ten

Kings of Hell Sutra handscroll. China;

Song dynasty; 1150 - 1200 Ink color, and

gold on paper. H. 28.0 cm. Freer Gallery

of Art, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C.

Pl. 73. Buddha

Preaching the Law, frontispiece to a Ten

Kings of Hell Sutra handscroll. China;

Song dynasty; 1150 - 1200 Ink color, and

gold on paper. H. 28.0 cm. Freer Gallery

of Art, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C.

The Metropolitan scroll contains the middle section (Chapters 5 through 9) of the sutra. Manjusri’s call on Vimalakirti occurs in Chapter 5. The assembly shown in the frontispiece painting is set on a raised platform, enclosed rather awkwardly by walls (abruptly curved on the left side) and approached by a ramp. The elderly Vimalakirti,seated on his sickbed,clearly dominates the composition. He holds a peacock-feather fan in his right hand and places his left hand on an armrest. To his proper left is the diminutive figure of Manjusri, seated on a lotus pedestal atop his vehicle, the lion. Kneeling directly in front of Vimalakirti is the even smaller figure of the monk Sariputra, who appears in Chapter 6. When Sariputra enters the assembly and finds no seat in the room, Vimalakirti reads his thoughts and asks if he has come here for a seat or to hear the Buddhist law. The wit he displays in this interchange, as well as his extraordinary intellectual powers, endeared the Indian sage to his Chinese audience.

A woman holding a bowl of flowers stands to the proper right of Vimalakirti. She makes her appearance in Chapter 7:“A goddess who had watched the gods listening to the Dharma in Vimalakirti’s room appeared in bodily form to shower flowers on the Bodhisattvas and the chief disciples of the Buddha (in their honor). When the flowers fell on the Bodhisattvas, they fell to the ground, but when they fell on the chief disciples, they stuck to their bodies and did not drop in spite of all their efforts to shake them off.”20 The disciple Sariputra could not shake the flowers off because of his differentiation between the flowers (i.e., form) and the absolute (formlessness) which he sought, but the goddess pointed out to him that the flowers do not differentiate and that it is Sariputra alone who gives rise to this differentiation. She taught him to stop all differentiation so that he “could wipe out space and time to agree with supreme enlightenment.”21 The small narrative scenes around the bottom of the platform may represent various mundane activities that are indicative of Vimalakirti’s role as a householder and sage. To the left the door at the top of the ramp is opened by a group of visitors led by Vasu with his crook. The brahmin Vasu, who renounced his kingdom to become a hermit, is a kind of philosophical counterpoint to the goddess of wealth and beauty who showered flowers on the gathering. Aschwin Lippe noted that the last figure in this group wears a hat peculiar to Yunnan and may represent the donor.22 Certainly Vimalakirti represented the ideal precedent and model for devout lay Buddhists such as the prime minister or the emperor of Dali. The scene of the debate between the sage and the bodhisattva figured prominently in the well-known Dali handscroll of 1180 in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, and the founder of the kingdom, the first of a hereditary dynasty, was believed to be a divine ruler, chosen by a miraculous revelator, the White-robed Avalokitesvara.23

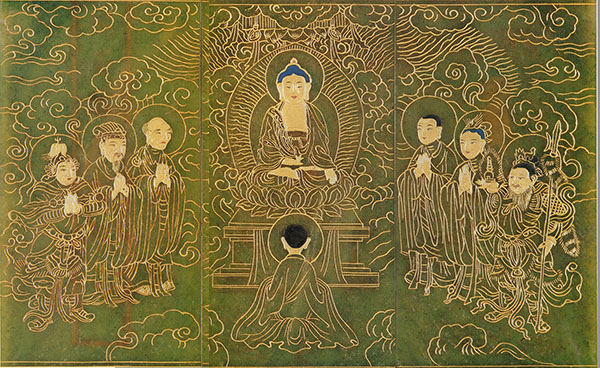

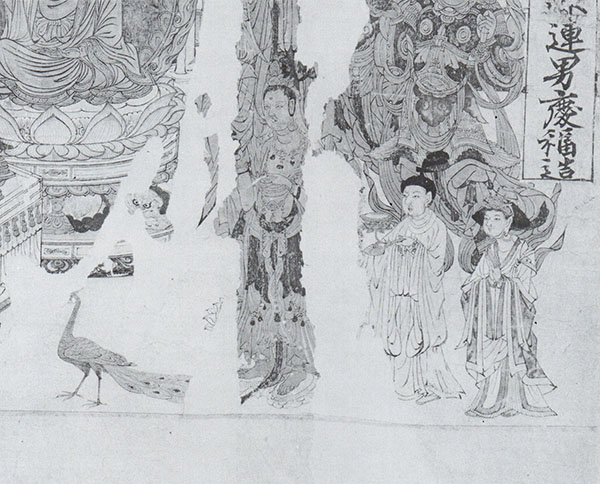

A second scroll associated with the Dali kingdom is a Ten Kings of Hell Sutra in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Pl. 73). Although badly obliterated, especially in the text section, the frontispiece composition in which Yama, fifth king of hell, kneels in front of Sakyamuni, is still impressive. The Buddhist assembly is set once again on a raised platform defined by balustrades and a flight of steps. Rays of light emanate from the Buddha’s halo, and apsaras (flying angels) flank the canopy suspended overhead. Sakyamuni is attended by two young monks (perhaps Ananda and Kasyapa), the four Guardian Kings, and a host of bodhisattvas. Whereas the celestial figures are richly painted in gold, a man and woman in the lower-right corner, slightly smaller in scale, are rendered in outline only (fig. 93). They may represent the donors mentioned in the label at right.24 Moritake Matsumoto has described many signs of the Dali style depicted here, beginning with the peculiar facial features of the figures represented in three-quarter view: the large hooked nose, bulging eyes, highly developed chin and jaw, and small recessed lips.25 Other similarities to the long scroll in Taiwan include the proportions of the double-flame halo and inclusion of a jewel in the topmost flame. The bearded Yama, the two flying cranes, even the conspicuously placed peacock have their counterparts in the scroll of 1180. A rather primitive perspective and awkward spatial organization of architectural elements are inherent in the Dali style, which is definitely archaistic and retarded by comparison with mainstream contemporary Chinese painting.

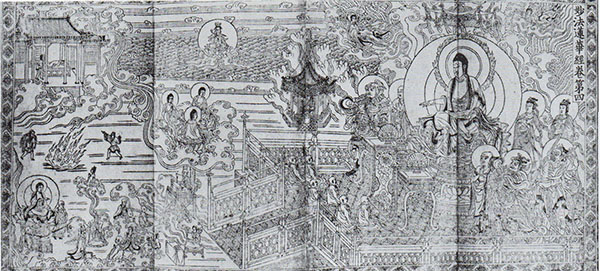

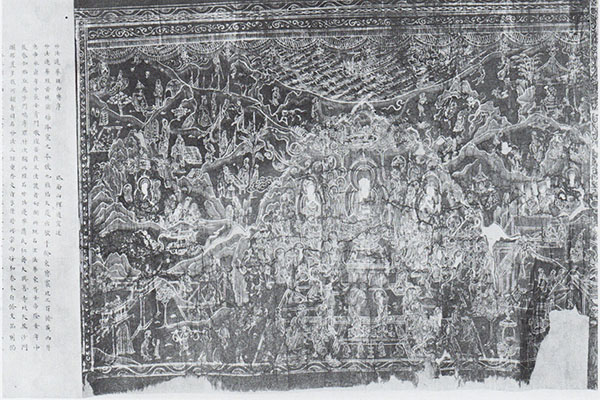

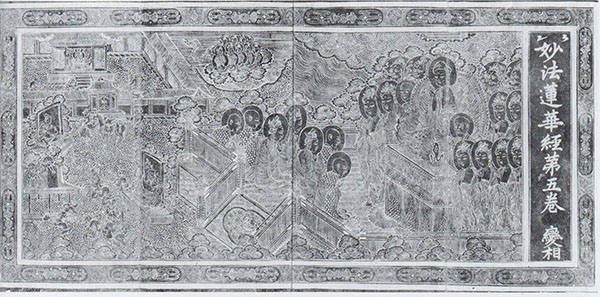

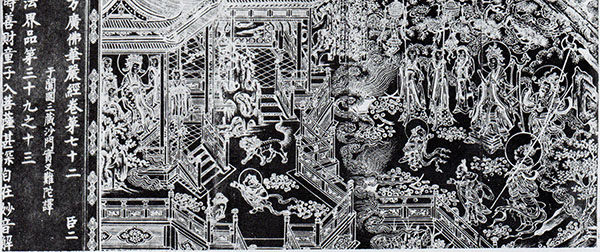

By the Song dynasty (960-1279) the preferred format for most Chinese manuscripts was that of the folded book, which proved to be more practical and handy than the long rolled scroll. To make a folded book, each sheet of paper would typically be folded four times to make five narrow pages, including two double pages. The result was essentially an accordion- pleated handscroll. The typical sutra frontispiece in booklet form covers four to six pages (or two to three double pages) and perpetuates the horizontal composition with the Buddha and attendants on a raised platform filling nearly two-thirds of the composition. In the four-page illustration preceding Volume 4 of a seven-volume Lotus Sutra printed and published in Zhejiang, miniature vignettes from Chapters 8 through 13 fill the space in front of the platform (fig. 94). Chapter 8, “The Assurance of the Future Buddhahood of Five Hundred Disciples,” is illustrated in the upper-left corner with the parable of the rich host who fastens a gem inside the garment worn by his poor friend, who has fallen asleep drunk. The next day the poor man departs for another country never suspecting the wonderful gem he carries with him. This gem is the wisdom of the Buddha, latent in the minds of his followers. Chapter 10, “The Teacher of the Law,” is represented by the monk reading scriptures from a high puipit at the foot of the ramp leading to the Buddha’s platform. According to the text anyone who reads or recites the Lotus Sutra will be worshiped as Buddha, and those who hear the law from him will be able to attain perfect enlightenment instantly. Just below the monk, at the entrance to the ramp, a woman is seated on a low circular stool, behind a table with scriptures, reading a sutra. This is Yasodhara, one of six thousand nuns who are assured of future Buddhahood in Chapter 13 and who promise to propagate the Lotus in the future. The small hexagonal stupa appearing at the center of the composition, its open door revealing two Buddhas seated side by side, is a scene from Chapter 11. While Sakyamuni is preaching his sermon a stupa springs miraculously from underground and the voice of Buddha Prabhutaratna is heard from behind its closed door. Buddhas come from far away to see the door opened (they are represented by the three small Buddhas arriving in a swirl of clouds just to the left). Sakyamuni enters the stupa and sits down beside Prabhutaratna, who has come to hear the Lotus Sutra. From the same chapter is the episode at the center of the left edge of the frontispiece, where a man carrying a load of dry grasses toward a bonfire is warned of danger by the agitated gesture of a passerby. This illustrates the Buddha’s admonition that

It is not difficult

To shoulder a load of hay

And stay unburnt in the fire

At the end of the kalpa of destruction.

It is difficult To keep this sutra And

expound it even to a person After my

extinction.26

Chapter 12 is represented by two successive images. The first is the figure of Manjusri who, seated on a thousand-petaled lotus flower, emerges from the ocean palace of the dragon- king to inform the Buddha of countless beings he had converted and to praise especially the young daughter of the dragon- king. He is shown enclosed in a bubblelike body halo. In the lower-left corner the precocious girl kneels in front of Sakyamuni. The text tells us that the skeptical Sariputra questions her qualifications for enlightenment, saying that“the body of a woman is too much defiled to be a recipient of the teachings of the Buddha.... A woman has five impossibilities. She cannot become 1. the Brahman-Heavenly King, 2. King Sakra, 3. King Mara, 4. a wheel-turning-holy-king, and 5. a Buddha.”27

The girl then proves herself by offering a gem to the Buddha, who accepts it immediately. The gem is the symbol of her superior wisdom, and its quick acceptance a guarantee of her enlightenment.

Thereupon the congregation saw that the daughter of the dragon-king changed into a man all of a sudden, performed the Bodhisattva practices, went to the Spotless World in the south, sat on a jewelled lotus-flower, attained perfect enlightenment, obtained the thirty-two major marks and the eighty minor marks [of the Buddha] and [began to] expound the Wonderful Law to the living beings of the worlds of the ten quarters.

She had become a Buddha.

In the Song print the jewel held by the girl is indistinct, but a tiny male figure clearly rises from a cloud above her head. It may be thought a small consolation to attain Buddhahood at the expense of undergoing a sex change, but in the male- oriented society that formulated the Lotus Sutra, woman was cast in the role of impure temptress, inferior mentally, physically, and spiritually. In addition, the female anatomy lacked the crucial twenty-third of the thirty-two major signs of perfection that distinguish the body of a Buddha.

The narrative is unravelled with even more didactic literalism in a painted Song Lotus Sutra tentatively dated to the first half of the twelfth century and now in the Seikado Foundation, Tokyo.28 This little folding booklet, whose sketchy illustrations cover twelve double pages preceding the text, is protected by carved wood covers with a vajra border and a title plaque supported by a lotus (fig. 95). A dedicatory inscription reveals that the covers were commissioned by a female member of the jin family from Pengcheng in Hebei Province. The project was supervised by the priest Daoyin. Twenty-six lay devotees, including high-ranking government officials, participated in transcribing the text.

The loosely organized vignettes (fig. 96) are identified by cartouches, in the manner of more informal wall paintings: at the bottom of the detail shown here Manjusri arises from the ocean on his lion mount accompanied by other bodhisattvas and at the center left edge dismounts to pay homage to the two Buddhas (Prabhutaratna and Sakyamuni) seated side by side in the stupa. At the upper right the daughter of the dragon- king kneels with her flaming jewel in front of Sakyamuni and his retinue, who are sheltered under a canopy of trees. Below, she reappears as a small male figure (a boy with hands folded in prayer), and at the center of the right edge of the composition she (now he) rises as a Buddha conveyed by a cloud toward a palace in “the Spotless World in the south.”

If the Song printed sutra cited above (fig. 94) is compared with a Yuan example of about 1346 (fig. 97) it is apparent that iconography and basic layout continue essentially un changed, despite some minor variations (the stupa is now a multi-storied pagoda and the positions of the daughter of the dragon-king at the bottom of the fourth page and monk reading scriptures at the bottom of the fifth page are reversed). The composition has become more painterly: in place of a schematic, linear striation demarcating the ground there are landscape elements such as a rocky hillside with jutting pine in the left foreground and a clearly defined shoreline. Moreover, the Buddha’s formal podium is replaced by billowing clouds. These innovations tend to create a softer,more naturalistic setting. By comparing a nearly identical Yuan painted example of comparable data (fig. 98) the ongoing interaction of printed and painted sutras becomes apparent. Because tiny errors in the gold and indigo version suggest the misinterpretations of a copyist, Miya Tsugio has speculated that the printed sutra served as the model.29

Generally, the Mongols, an alien, non-Chinese people, made no significant contribution to the art of the brief Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) but Tibetan and Nepalese stylistic elements were imported along with the esoteric lamaist variety of Buddhism favoured by them.30 A nearly complete Tripitaka printed in 6,363 volumes between 1231 and 1322 has a small number of frontispiece illustrations (fig. 99) that are hailed as the missing link in Yuan art because they document the importation of a Tibeto-Nepalese style at a date much earlier than previously imagined. Published by the Yansheng Yuan, a monastery on Qisha (Sand Holm ) Island on a lake in Jiangsu Province near Suzhou and Hangzhou in southeast China, it was actually begun in the Southern Song period (1127-1279) with support from devout local citizens, but production broke off between about 1265 and 1297, a period roughly corresponding to the reign of Kublai Khan.

Printing resumed around 1300; one donor who gave large sums of money toward completion of the engraving and printing of the Qisha Tripitaka was a member of the lamaist clergy with a Tibetan education who was probably from the Xixia kingdom in northwestern China. This man, Guanzhuba, was responsible over the years for distributing vast numbers of both printed and painted sutras as well as gilt images, not to mention offerings of food to one hundred thousand monks. In 1307, at the end of a long and detailed resume of his good deeds (a sort of spiritual curriculum vitae), he cited his hopes and aspirations as follows:

In accumulating these scraps of merit, may I attain vast non-action and return to true thusness, to the splendid limits of reality, the supreme land of the Buddha, which is enlightenment (bodhi). May the master of the teaching in the west, the Buddha Amitayus, the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta, and the pure ocean of the host of bodhisattvas pray that the Emperor live 10,000 years and the Empress likewise, may the heir to the throne and the princes live in good fortune for 1,000 springs; I pray for the Imperial Preceptor, King of the Dharma. May the foundations of prosperity be strengthened, may the times be clear and the way flourish. . .. May sons be filial and subjects faithful. May the five cereals ripen and may the people multiply. Above there is the zenith, but below there is no limit. May all beings that have life in the dhramadhatu attain the way of the Buddha.31

Some illustrations attached to the Qisha Tripitaka scrolls with colophon dates in the early fourteenth century include the names of the painter (or designer) and carver. These artists and artisans are believed to have worked in Hangzhou (Zhejiang Province), an active lamaist center, around the year 1300.32 In the frontispiece shown here the name of the artist, Chensheng, can be found in the lower-right corner. Illustrations were printed separately from the text, on different paper, and their placement seems to be random. In this scene, Sakyamuni, wearing the patchwork robe of a mendicant, sits on a lotus placed on a square dais and preaches to an assembly of monks and deities. His hands display the gesture of turning the Wheel of the Law, or preaching. Flanked by his chief disciples, the monks Ananda and Kasyapa, he tui;ns his head toward the seated goddess Sitatapatra Aparajita, a cosmic form of Tara. The wasp-waisted, sensuous figure holds her emblem, a jeweled umbrella.

There was continual communication and artistic exchange between the Mongol court and Tibet during the Yuan dynasty, and this contact extended into the early Ming dynasty (1368- 1644), especially during the Yongle (1403-24) and Xuande (1426-35) eras. The dynamic Emperor Chengzu (1360-1424), in particular, expressed feelings of deep reverence for the lamaist spiritual leaders. His interest in Tibet was not confined to political manipulation, and contact with Tibetan Buddhists was greatly expanded during his reign. Tibetan monks resided in Nanjing and Beijing; Tibetan texts, including the Tibetan canon, were printed in northern China; and early fifteenth-century sculptures of the Sino-Tibetan style are believed to have been produced under imperial command in government workshops staffed by Tibetan and Nepalese officials and artisans. Furthermore, there were endless trade missions, both lay and religious, between Tibet and China.

The frontispiece to a Kshitigarbha Sutra of the Hsuande era, dated 1429 (fig. 100), reflects a more full-blown Tibetan style. The sutra is printed in the form of folded books in three volumes and may have belonged to the palace edition of 6,361 volumes known as the Beizang, or Northern Tripitaka, initiated by Emperor Chengzu around 1420, at the time of the removal of the Ming court from Nanjing to Beijing (the northern capital). The set was not completed until 1440, and it is said that only the best artisans and materials were employed in the production of this work.33

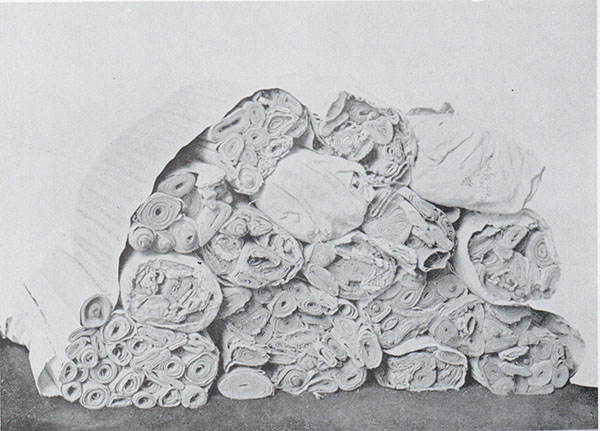

Characteristic of the Chinese tradition was the production of sutra covers made from brocade where symbols and texts were woven with great delicacy. Among the finest of such woven material is a set of five pairs of sutra covers in the Seattle Art Museum from the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911) (Pl. 74).34 The kesi (k’o-ssu) technique of tapestry weaving in silk that is used here is unique to China. The term is generally applied to woven interpretations of paintings and calligraphic inscriptions as developed in the Song dynasty. Jean Mailey considers that “the distinguishing characteristic of silk tapestry in China is its capacity for recreating in woven silk the effects of a variety of media. . . .Yet the woven medium of silk tapestry in reproducing each of these effects, at its best, gives each a special character of its own. Only in a country where sericulture and silk-weaving were held in equal regard with the other arts could this have been possible.”35 Kesi is characterized by discontinuous wefts causing small slits between the adjoining areas of color to produce an engraved effect to the design. The silk-tapestry technique became a treasured weave by the eighth century; Tang dynasty examples are found among the imported treasures of the Emperor Shomu in the Shosoin, Nara, and among the Dunhuang banners found by Sir Aurel Stein in Central Asia. In the Song dynasty, paintings were reproduced in silk tapestry without any additional embellishment but, in keeping with the richer, more ornate taste of the Qing dynasty, portions of the woven design of the Seattle covers were enhanced with gold, paint, and ink.

The Seattle covers also demonstrate the continued interaction between Chinese and Tibetan artistic traditions under the Manchu. Judging by their size and horizontal shape they were originally intended to cover the title page of the stacked folios of a particularly lavish Tibetan manuscript, perhaps one commissioned as a dowry item for private devotional use. Often three orfour layers of Chinese silks covered a title page, affixed along the top edge with a strip of paper and glue. The Seattle set was either detached or never used. A wood outer cover, probably encrusted with precious stones, would have completed the ensemble.

Each of the covers is ringed by a traditional Chinese motif, a symmetrical design of elongated, striding dragons shown in profile, with flaming jewels. Three of the five pairs have intricately worked designs of the eight Buddhist emblems: the wheel, conch, umbrella, canopy, lotus, paired fish, vase, and endless knot, each resting on a lotus blossom. The other two pairs are inscribed with Buddhist texts, one in Tibetan and one in Siddha script, an ornamental form of Indie script used exclusively by Chinese and Japanese monks for writing dharanis.

The Tibetan text is a transliteration of a Sanskrit invocation (dharani) or prayer to the tantric goddess Sitatapatra (see fig. 99). All dharanis and mantras are preserved in the holiness of their original Sanskrit sounds, even when transliterated into Tibetan or Chinese. Mystical power is thus attached to the sounds themselves, even when their Sanskrit meaning may be unknown to the East Asian Buddhist. The invocation of Sitatapatra summarizes the mystical treatises covering the meditations, rituals, mandalas, and evocations of this goddess as found in the Tibetan scriptures. The mandalas of this goddess show her with nineteen hundred heads and arms, surrounded by seventeen or twenty-seven Buddhas, and white umbrellas or parasols (emblems of royalty] adorning the borders of the universe. Her evocation (sadhana) is included in the tantric teaching and practices of all four Tibetan monastic orders but is especially venerated in the Gelukpa monasteries. The dharani on the Seattle sutra cover has been translated as follows:

[Pronounce the Invocation] thus:

Om! Anale! Anale! [god of fire and wind]

Khasame! Khasame! [god of rest and ease]

Vaire! Vaire! [god of revenge]

Some! Some! [god of Vedic soma juice]

Empowerment of the power of all Buddhas,

hail!

Om! Lady of the white umbrella! Diadem of

all Tathagatas! Hum! Begone [evil spirit]!

Hum! Mine! Hum! Within! Hail!36

The last two lines are repeated twice.

Chinese influences on the art of Tibet have been discussed in Chapter 4. Under the Manchu, another non-Chinese dynasty, Tibetan Buddhism and lamas continued to exert considerable influence both at court and important Chinese monasteries. Tibetan books were copied in many of the Chinese monasteries, and the lamas preferred to use Chinese silks to cover both their thankas and their sutras. Chinese factories produced brocade sutra covers and silk curtains for the use of local temples such as the Yonghegong (Yung-ho-kung) in Beijing and also for export to Tibet. A particularly fine example of such a silk curtain can be seen on a Tibetan folio now in the Newark Museum (fig. 101). The smallest topmost silk is a polychrome brocade with dragon, cloud, lotus, and citron motifs on a black ground; the middle layer is a plain red silk; and the bottom is a yellow damask with a design of flowers on fretwork. While Chinese and Japanese handscrolls are often given brocade outer covers, the use of layers of elaborate silk curtains to protect the title pages of sacred books appears to have been a peculiarity of the Sino-Tibetan tradition.

Among the most precious (if least practical) Chinese religious texts are those incised on jade. One of the finest jade books, in material and technical execution, is a set of fifty- three tablets in the Chester Beatty Collection, Dublin (Pl. 75).They are of highest quality green nephrite cut to extreme thinness—three millimeters—and incised on both sides with the full text of the Diamond Sutra.37 Jade had been used as a writing material by Chinese emperors for thousands of years. According to the Confucian book of ritual, the Li Ji, written in the early centuries B.C., the emperor carried a long, thin, jade tablet hanging from his waistband as a sort of luxurious portable notebook. Characters might be written in ink but were often incised into the jade with a chisel, the theory being that jade would last forever (unless accidentally broken, of course) and that words incised into a jade tablet would also become immortal. Such jade tablets were first associated with sacrifices to heaven, imperial ceremonies to placate the spirits and invoke peace and prosperity. Often these tablets were provided with holes so that they could be threaded with a cord to facilitate assembling the thin slips of jade into a hinged-book format. The nephrite itself was brought overland at great expense from Chinese Turkestan to the imperial workshops; all jade books are thought to be imperial commissions, with the majority of extant examples dating from the reign of the Qianlong emperor (r.1736-95). Their content might be Buddhist texts, official records (proclamations awarding posthumous ranks and titles to a deceased relative, for example), or imperial notes and poems.

When placed side by side, the first three folios or tablets of the Chester Beatty Diamond Sutra form the frontispiece, a hieratic, symmetrical compostion showing the enthroned Buddha Sakyamuni flanked by heavenly guardians of the law (including Vaisravana at the far left) and other worshipers. The incised lines of both frontispiece and text are filled with gold; the frontispiece also contains touches of black, blue, and red pigment. The narrow width of the folios, linear design in gold, and wide, double-ruled upper and lower margins all re-create the appearance of a more conventional indigo and gold sutra in the standard folding-book format. Fifty-three tablets are stacked in a tightly fitting custom-made box of brown slate (fig. 102). The book is dated 1733 and signed by the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723-35). Inscribed on the last folio are the words: Engraved with heartfelt respect for my disciple, the serene and wise prince, to ensure his true happiness. The prince in question is thought to be Hongli, the emperor’s fourth son, who adopted the reign title Qianlong after ascending the throne two years later in 1735, at the age of twenty- four.

Korea

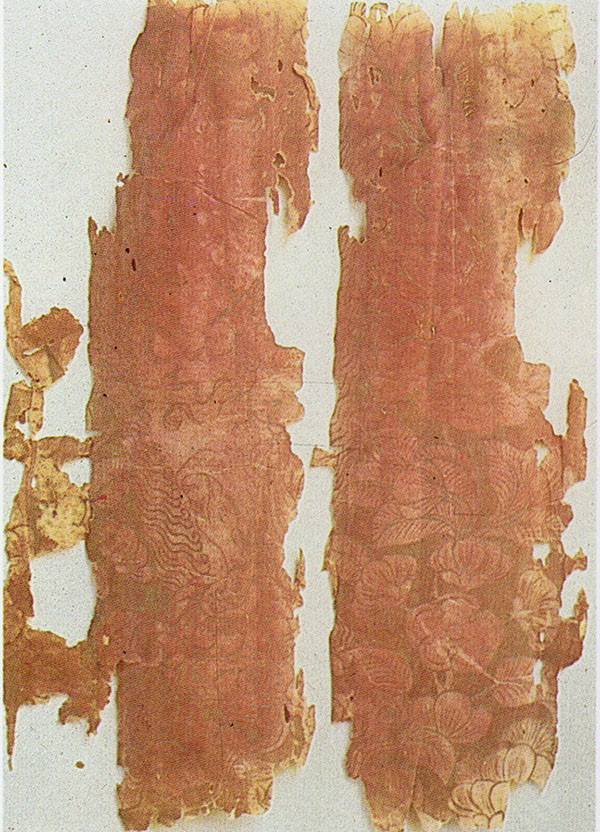

Buddhism was introduced to Korea in the fourth century and was subsequently patronized by the ruling elite for practical goals such as warding off calamities and protecting the nation against constant threat of invasion from the north. It became a powerful state creed during the Unified Silla period (668- 935), when kings and queens shaved their heads and became monks and nuns, but eventually lost its hold on the court when Confucianism became the official religion of the Choson (Yi) dynasty (1392-1910). Recently, two very early Korean scrolls from a set of the Avatamsaka Sutra have come to light and are attracting considerable attention because of their fine quality and presumed eighth-century date (Pl. 76).38 The text is written in thirty-four characters per line on white mulberry paper with ruled lines painted in gold. The axle is made of red wood, and roller ends are crystal. Fragments of purple paper beautifully painted with gold and silver ink have been preserved together with (but detached from) the text. The cover image includes a conventional floral scroll and a heavily muscled guardian figure backed by a halo of flames; the frontispiece shows a Buddha and attendants enthroned in front of a heavenly palace. Concrete evidence has not yet been found to establish a connection between the painted fragments and the text, but other early examples of attaching decorated frontispieces to plain paper are known. Furthermore, the full-bodied figures, drawn with crisp iron-wire lines, are compatible stylistically with an eighth-century date and bear comparison with contemporary Chinese and Japanese Buddhist paintings.

A colophon at the end of one scroll states that the project was begun in the eighth month of 754 and completed in the second month of the following year. The rites preceding the transcription are described in detail, and the name of the painter is listed with those of the calligraphers and other craftsmen who participated in the making of the work. The scrolls may originally have been enshrined as reliquary items within the base of a large stone pagoda.

Merchants, monks, and pilgrims traveled the seas between China, Korea, and Japan with regularity, carrying trade goods as well as Buddhist scriptures while disseminating iconography and new styles of painting. In the ninth century, at the height of the growth of the Silla kingdom, the Japanese monk Ennin noted the presence of a Korean trade ship with Chinese celadons in a Japanese harbor; he also observed Korean activity in the coastal communities of central China. In fact, early illustrated sutras from East Asia are so rare, and cultural interchange so intense, that it is often difficult to determine the nationality of the few works that survive. Koryo examples from the tenth and eleventh centuries were for the most part destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1231.

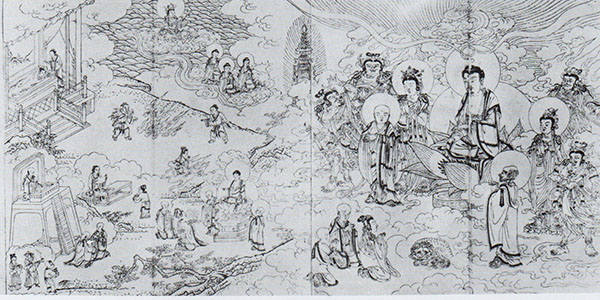

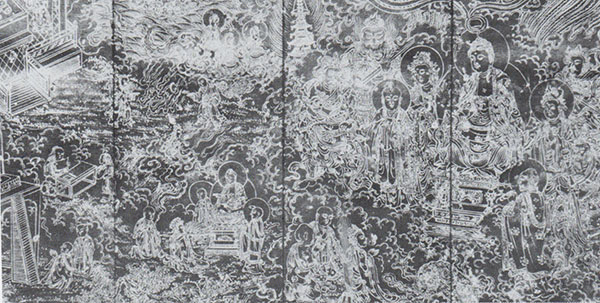

One scroll whose identity is still debated is a Lotus Sutra now in a Japanese Shinto shrine, Danzan Jinja in Nara Prefecture (fig. 103J. It dates from approximately the eleventh or early twelfth century, but whether it is Koryo (918-1392),Song, or even Japanese is open to question.39 The text, in seven volumes, is transcribed in one scroll with thirty-four miniature characters per line in ink on plain paper. The fringed and tasseled curtain of a stage set runs across the upper edge of the painting,and fifteen small scenes unfold in rich theatrical detail around a central Sakyamuni preaching on Vulture Peak. The composition, in which scenes are separated from one another by space cells formed from the hollows and crevices of mountains, recalls that of many early wall paintings of the Lotus Sutra at Dunhuang. The entire upper third of the painting is filled with five episodes from the familiar Chapter 25, with special emphasis on the dramatic third peril, a storm- tossed boat at sea.

The carving of wood printing blocks for the Tripitaka Koreana (in emulation of the Song edition, acquired as a gift from the Chinese emperor in 991) was completed under King Hyong ong (r.1009-31) as a kind of spiritual bulwark against the impending Mongol invasion. All copies were soon lost to fire, but a new edition in 6,529 volumes (some 160 thousand pages) was produced between 1236 and 1251; more than 80 thousand of the original wood blocks are still preserved at the Haeinsa Monastery. Koryo Buddhism was patronized by the royal family, however, and the transcription of ornamental luxury versions continued unabated. The earliest surviving Korean sutra with text transcribed in gold on indigo was commissioned in 1006 by the dowager queen mother together with a relative and trusted retainer. Scholars speculate that it was the product of an official bureau for sutra transcription mentioned in the History of Koryo (Koryosa).40 In 1185 an entire Tripitaka in 5,048 scrolls was written in gold ink with prayers invoking the safety and prosperity of the nation. These were stored in 593 sutra boxes ornamented with mother-of- pearl inlay, red lacquer, and gold.

In the thirteenth century Koryo surrendered to the Mongol rulers of Yuan China, and a Mongol princess, the daughter of Kublai Khan, was married to the Korean king, Chungnyol Wang (r. 1274-1308), initiating a long period of intermarriage and direct contact between the two nations. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the Chinese empress (or dowager empress) and the Koryo queen were intimately involved in numerous sutra projects with an emphasis away from dedications expressing concern for enemy invasions and in favor of those aimed at personal salvation, redemption of deceased family members, and long life.

The History of Koryo records the founding of a new government-sponsored workshop for the transcription of gold and silver letter Tripitakas at the residence of a high-ranking official in the third month of 1281, the month the Yuan empress died. A gold letter Tripitaka initiated and completed in 1289 may have been sponsored by her daughter, the Koryo queen. At least four thirteenth-century Tripitakas in silver characters on indigo paper, commissioned by the royal family, have survived, all were presumably based on the printed Tripitaka Koreana, valued for its accuracy. In addition many private projects were sponsored by wealthy members of the aristocracy and clergy; the Lotus Sutra and the Avatamsaka Sutra in folding-book format were favored for these smaller dedications.

Koryo painted sutras show the influence of both Song and Yuan printed models. The iconography of the Korean Lotus Sutra dated 1373 in the National Museum of Korea in Seoul (fig. 104),is probably drawn from a Yuan printed counterpart, such as the set datable to around 1346 (fig. 97), while antecedents for the general composition, border frame, and rather insistent linear technique can be found in Song sutras (see fig. 94). In the upper-left corner is the parable of the great king from Chapter 14. The king requested the rulers of neighboring countries to surrender to him. They did not consent, so he fought and conquered them. He then granted various rewards to his men according to their merits, saving the best for last: the soldier of extraordinary merit received a brilliant gem (the teachings of the Lotus Sutra), which the king had kept in his topknot. In the picture the soldier’s horse is waiting by the front gate of the royal palace.

The many bodhisattvas flying in on a cloud to the right of the palace are those who appear miraculously to greet the Buddha in Chapter 15. Chapter 17, “The Variety of Merits,” is represented by a monk reading the sutras (and thereby obtaining innumerable merits) and by carpenters in the lower-left corner raising bundles of tiles to complete the roof of a monastery. According to the text anyone who keeps this sutra should be considered to have already built a monastery installed with thirty-two beautiful halls, provided with delicious food and drink, with accommodations for 100 thousand people, with promenades, pools, and gardens.

The last portion of the Avatamsaka Sutra is the Gandavyuha, the story of a young boy’s travels in search of supreme truth, a sort of Buddhist pilgrim’s progress. The search takes the boy, Sudhana, through different parts of India where he accumulates wisdom by visiting more than fifty spiritual guides, each with a different message. In an example in the New York Public Library (Pl. 77), his small figure can be seen standing in a posture of devotion just to the left of the cartouche in the lower-left corner. Written in India, in eighty volumes, the Avatamsaka Sutra was translated into Chinese (the language used in this manuscript] in the fifth century and was transmitted from China to Korea in the seventh century by the famous monk Uisang (625-702], founder of the Hwaom (Avatamsaka) sect of Buddhism in Korea. The scripture is one of the longest and most complex in the Buddhist canon and was highly venerated in official circles throughout East Asia.

Koryo sutras have several distinctive characteristics. The paper is heavier and more durable than that of China or Japan and feels stiff to the touch. The color of the paper is a deep blue-black, popularly known (in Japan) as mayuzumi (eyebrow blackener),although there are also examples in gold ink on white, brown, purple, or salmon-pink paper. Frontispiece paintings are typically spread over the first four leaves of a folded book, and the text is written in six lines per page. Illustrations are painted in either gold or silver (never both together); gold predominates by the thirteenth century even when silver is used for the text. Upper and lower margins are generous with more space given to the former. The title is written prominently at the right edge of the frontispiece as well as at the center of the outer cover, and a succession of three- pronged vajra forms the border encircling the illustration. Gold pigment gleams with a fine metallic sheen, evidence of laborious polishing with ivory or buffalo horn. These features all endow the painting with a special dignity and balance.

A uniquely Korean trait is the tendency to fill virtually the entire surface with intricate small-scale patterns, leaving only faces, hands, and halos untouched by the almost mannered exuberance of densely spaced dots, swirls, and striations. In plate 77 the drapery seems to have dematerialized into a maze of interlocking, coiled springs. Rows of stylized snowflakes or stars float in front of horizontal ruled lines demarcating the heavens, and a peculiar little M-shaped stroke is used repetitively to fill empty spaces, including drapery.

Koryo sutra copyists, patronized by the highest levels of society in their own country, were equally esteemed at the Chinese court. In 1290 the Yuan emperor invited one hundred Koryo monks to spend a year at a temple in the capital at Datong to transcribe a Tripitaka in gold ink. This was only the first of many such groups of copyists to be summoned to China.41 Conversely, the Yuan dowager empress often funded large-scale transcription projects in the Koryo capital. It is hardly surprising that many Korean stylistic features are reflected in an Avatamsaka Sutra sponsored by priest Huiyue of Wanshouchan Temple at Mount Zhongnan in Changan, China, in 1291, a year after the arrival of the Korean copyists.42 Four scrolls from the original set, painted in silver on indigo, are preserved in the Kyoto National Museum (fig. 106). According to his colophon, Huiyue shaved his head and became a monk at age nine, rose to a high position in the Buddhist clergy, but reached the point where, disillusioned with the privileges of his rank, he began to discard personal property, gave away 108 clerical robes, commissioned fifty-three sets of the Avatamsaka Sutra, contributed to the printing of a Tripitaka, and personally transcribed the twenty-eight chapters of a Lotus Sutra, among others. The Chinese frontispiece paintings in the Kyoto National Museum are, on the whole, more naturalistic and less busy than their Koryo counterparts; nevertheless, they seem to provide a remarkable instance of the influence of Korean art on that of China.

A handful of Koryo sutra boxes (Pl. 78) preserved outside Korea seems to have Japanese provenance, suggesting that they may have come from a Buddhist library looted by the soldiers of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98), the dynamic general who successfully unified Japan at the end of the sixteenth century.43 He mobilized the nation lor two large-scale invasions ot Korea in the 1590s, devastating much of that nations’ cultural heritage and returning with a rich array of war booty. Although rare today, the boxes were evidently produced in some quantity, probably in government-sponsored workshops. The decoration of intricate, small-scale stylized chrysanthemums inlaid in iridescent mother-of-pearl is obviously related to the dense linear patterning of contemporary Koryo painting.

The preference for tactile, graphic surface patterns and repetitious designs appears to be an indigenous Korean aesthetic impulse. Regularized, abstract, linear patterns appear from the Bronze Age. Korean bronze mirrors dating from as early as the second century B.C. are covered with highly sophisticated geometric motifs based upon triangles, lozenges, and concentric circles executed in a maze of fine raised lines bearing almost no relation to Chinese prototypes. Similarly, Koryo celadon, elaborate and artistocratic in character, is inlaid with brown and white slips in a technique that represented a radical departure from Chinese celadon. The small black-and- white patterns became very complex by the thirteenth century. These design impulses were popularized later when courtly celadon evolved into punch’ong ware featuring surfaces of endlessly repeated incised and stamped dots applied with the speed of mass-production techniques and seen through a haze of hastily applied milky white slip.

Korean art is generally closer in feeling to Chinese art than to Japanese art. As observed by Lena Kim Lee, “The stylistic changes and the philosophical content of Korean paintings follow closely the changing patterns found in Chinese paintings. The general nature of Buddhist art in Korea,including its rise and decline,is also similar to that of China”.44 Korea’s artistic role is the more complex for having facilitated the flow of East Asian civilization from China to Japan; moreover, her own artistic movements frequently influenced the art of Japan. Despite the magnetisim of its highly developed neighbor and a tradition of continuous cross fertilization, Korea sustained a cultural identity of its own, and Koryo sutras, in particular, have a unique and distinctive beauty. The few Korean illustrated manuscripts that have survived, taken together with the literary evidence, indicate that Koreans were no less zealous than Buddhists elsewhere in copying and embellishing the sacred books.